People's Democracy

People's Democracy

(Weekly

Organ of the Communist Party of India (Marxist)

No. 45

November 06, 2005

(Weekly

Organ of the Communist Party of India (Marxist)

|

Vol.

XXIX

No. 45 November 06, 2005 |

On October 24, 2005, the CPI(M), CPI, RSP and Forward Bloc submitted the following note to the UPA-Left Coordination Committee on the issue foreign direct investment (FDI) in the retail trade sector.

THE UPA government is considering the opening up of the retail trade sector to FDI. The NDA government had also proposed steps to open up this sector to foreign investment during its tenure. Multinational retail chains like the Wal-Mart have been lobbying with the government in this regard. The Left parties, however, believe that allowing FDI in retail trade would have a negative impact on the already grim domestic employment scenario. Since employment generation is the cornerstone of the Common Minimum Programme of the UPA, inviting foreign capital in sectors, which would have a debilitating impact on domestic employment, would go against the spirit of the CMP. Moreover, there are other serious issues related to FDI in retail trade that warrant greater caution.

The Fragmented Retail Sector In India

Retail trade contributes around 10-11 per cent of India’s GDP and currently employs over 4 crore people. Within this, unorganised retailing accounts for 96 per cent of the total retail trade. Traditional forms of low-cost retail trade, from the owner operated local shops and general stores to the handcart and pavement vendors, together form the bulk of this sector. Since the organised sector accounts for less than 8 per cent of the total workforce in India and millions are forced to seek their livelihood in the informal sector, retail trade being an easy business to enter with low capital and infrastructure needs, acts as a kind of social security net for the unemployed. Organised retailing has witnessed considerable growth in India in the last 10-12 years and is growing at a much faster rate than the overall retail sector. This trend of an increasing share of retail trade coming under the organised sector inevitably causes displacement of small retailers in the unorganised sector and affects their livelihood. This needs to be kept in mind while discussing the impact of FDI in retail trade.

According to the Fourth Economic Census, 1998, out of a total of 18.27 million non-agricultural own account enterprises (enterprises normally run by members of a household without hiring any worker on a fairly regular basis; hereafter OAEs), which constituted 68 per cent of all non-agricultural enterprises, retail trade dominated among all major activity groups netting 8.36 million OAEs accounting for 45.8 per cent of the total number of OAEs (see Chart 1 alongside). In rural areas retail trade accounted for 42.5 per cent of the total number of OAEs while in urban areas it accounted for 50.5 per cent of the OAEs. Retail trade also accounted for 27 per cent of the total non-agricultural establishments, with 18 per cent of the establishments in rural areas and 34.3 per cent establishments in urban areas being engaged in retail trade. A state-wise breakup of the distribution of non-agricultural enterprises in India (see Table alongside) shows that for most of the states retail trade accounts for the largest share of non-agricultural enterprises. In 1998 employment in retail trade (11.18 million) constituted 41.6 per cent of the total employment in OAEs (see Chart 2 alongside). In rural areas retail trade accounted for 38.2 per cent and in urban areas 46.4 per cent of the employment in OAEs. Retail trade also accounted for 7.36 million workers in non-agricultural establishments accounting for 10.3 per cent of employment in non-agricultural establishments in rural areas and 17.4 per cent in urban areas.

A comparison between the Economic Census of 1980 and 1998 further shows that the share of manufacturing in non-agricultural enterprises declined in the rural areas from 39 per cent in 1980 to below 25 per cent in 1998 and in the urban areas from 30 per cent in 1980 to less than 17 per cent in 1998. Employment growth in the manufacturing sector has been less than 5 per cent during this period. In this context the retail sector, especially the unorganised retail sector, has played a crucial role in the absorption of labour. The situation has been lucidly described by Mohan Guruswamy et.al. in their article ‘FDI in India’s Retail Sector: More Bad than Good?’ (EPW, February 12, 2005). They write, “One of the principal reasons behind the explosion of retail outlets and its fragmented nature in the country is the fact that retailing is probably the primary form of disguised unemployment/underemployment in the country. Given the already overcrowded agriculture sector, and the stagnating manufacturing sector, and the hard nature and relatively low wages of jobs in both, many million Indians are virtually forced into the services sector. Here, given the lack of opportunities, it becomes almost a natural decision for an individual to set up a small shop or store, depending on his or her means and capital. And thus, a retailer is born, seemingly out of circumstance rather than choice. This phenomenon quite aptly explains the millions of small shops and vendors. The explosion of retail outlets in the more busy streets of Indian villages and towns is a visible testimony of this…. Yet, even this does not annul the fact that a multitude of these so-called ‘self-employed’ retailers are simply trying to scrape together a living, in the face of limited opportunities for employment. In this light, one could brand this sector as one of ‘forced employment’, where the retailer is pushed into it, purely because of the paucity of opportunities in other sectors.” (emphasis added)

Adverse Impact of FDI in Retail on Employment

In the absence of any substantial improvement in the employment generating capacity of the manufacturing industries in our country, entry of foreign capital in the retail sector is likely to play havoc with the livelihood of millions. It has been argued by some advocates of FDI in retail trade that since the retail sector is growing at a fast pace in India, entry of the multinational retail chains far from causing any labour displacement would actually generate more quality jobs. Such rosy pictures are painted on the basis of overenthusiastic projections of economic and consumption growth on the one hand and conveniently hypothesised market share for the organised retailers on the other. For instance, a McKinsey report on ‘Indian Growth’ projects an addition of 71 lakh jobs in the retail sector between 2000 to 2010 with the modern format retailers (e.g. supermarkets) accounting for 8 lakh jobs. However, the projection is based upon a projected 10 per cent GDP growth for the 10-year period and assumes a 20 per cent market share for the modern format retailers. In the case of a more realistic scenario of a lower GDP growth (current GDP growth is around 6 per cent) and a greater market share for the labour-displacing modern format retailers which is likely if FDI is permitted, total employment in the retail sector would actually shrink.

A back-of-the-envelope calculation can substantiate the point. If we take the total retail sales in India to be Rs 312180 crore approximately (which is around 11 per cent of India’s GDP at factor cost at current prices in 2004-05), turnover per employee for the Indian retail sector comes to around Rs 78045 (taking total employment of 4 crore). In contrast, the turnover per employee for Wal-Mart International comes to around Rs 7418332 (Annual Report 2005 of Wal-Mart puts the total sales figure for Wal-Mart International at 56277 million dollar, which at the current exchange rate comes to Rs 244804.95 crore approximately; total number of employees of Wal-Mart International according to their website is around 330000). Putting it simply, the annual turnover per employee of Wal-Mart International is nearly 95 times that of the average annual turnover per employee in the Indian retail sector. This gives an approximate estimate of the extent of job loss that can be caused by the entry of such multinational retail chains in the retail trade sector. (Estimates of the size of the Indian retail sector vary from Rs 400000 crore (ORG Gfk survey, 2001) to 1100000 crore (Chengappa et.al, 2003). Here a simple measure of 11 per cent of GDP has been followed, which is perhaps an underestimation. However, even if a much higher estimate of the retail sectors’ total annual turnover is taken, the conclusion that the annual turnover per employee of Wal-Mart International is many times that of the average annual turnover per employee in the Indian retail sector, would not change.)

The experience of Thailand, where entry of foreign capital took the share of organised retailing to 40 per cent within a span of a few years accompanied by widespread closure of small and traditional retail outlets, is pertinent in this regard. An ACNielsen report (2003) on the Retail Structure of Asia has shown that for all the South-East Asian countries that have allowed the multinational retail chains to operate (China, South Korea, Malaysia, Singapore, Taiwan and Thailand) the growth in the number of supermarkets have been invariably accompanied by a concomitant decline in the number of traditional grocery stores. China is often cited as an example where FDI in retail has generated a large number of new jobs in the 1990s. It is important to note in this regard that substantial deregulation of foreign investment in retail trade in China took place only in 2004. An Asian Development Bank document has in fact expressed apprehensions that rising competition in retail trade will lead to the decline of small private ventures, which operate in trade and food services in China.

(The Development of Private Enterprise in the People’s Republic of China, Asian Development Bank, available at http://www.adb.org/documents/studies/PRC_Private_Enterprise_Development/prc_private_enterprise.pdf )

In the developed countries too, the growth of organised trade in the retail sector has led to poorer societal outcomes. In the US, for instance, poverty has increased wherever Wal-Mart has an established presence or has expanded. A recent study found that counties in the US with more initial Wal-Mart stores in 1987 and with more additions of stores between 1987 and 1998 experienced either greater increases or smaller decreases in family poverty rates during the 1990s economic boom period. (Stephan J. Goetz and Hema Swaminathan, “Wal-Mart and Rural Poverty”, Paper presented at the American Agricultural Economics Association Annual Meeting, Denver, Colorado, August 1-3, 2004.) The study concludes that Wal-Mart stores drove out local entrepreneurs and community leaders. Another study also found that the entry of Wal-Mart reduced the number of small retail establishments and had a negative effect on wholesale employment in the US. (Basker, E. “Job Creation or Destruction? Labor Market Effects of Wal-Mart Expansion”, University of Missouri Working Paper, 2004.) A document Labor Productivity in the Trade Industry, 1987–99 prepared by the Office of Productivity and Technology, Bureau of Labor Statistics of the US also details the experience of the US in this regard. (http://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/2001/12/art1full.pdf) In the context of grocery stores the document states, “Consumers increasingly turned away from conventional grocery stores for their food purchases, choosing instead superstores and hypermarkets. In 1988, conventional grocery stores accounted for 42.8 per cent of all consumer expenditures for food at home; by 1998, that proportion had fallen to 13.4 per cent. In response to these changes in consumer spending patterns, the overall number of grocery stores shrank over the 1987-97 period — from 137,584 to 126,546, an 8.0 per cent drop.” In the context of apparel stores the document states, “Most of the three and four-digit SIC apparel store industries experienced a decline in the number of establishments and basically flat employment levels over this 12-year period. Most of the employment decline in the latter period came from family clothing stores.”

The fast growth of the organised retail sector experienced in India over the last few years has been based upon the consumption demand of the rich and upper middle classes, whose disposable incomes have risen considerably. Reportedly, around 450 shopping malls are already operating or under various stages of development across the country. Technological upgradation has also accompanied this growth in organised retail. However, it needs to be understood that over-dependence on such luxury goods consumption-led growth, which seems to be the basis of the economic vision underlying the arguments for allowing FDI in the retail sector, is counterproductive since it leads to growth of the “jobless” kind and is therefore unsustainable. Growth occurring in both the organized as well as the unorganised retail sectors simultaneously is a chimera. The former grows necessarily at the cost of the latter therefore making job loss inevitable. Therefore the government has to go beyond a narrow focus on the need to satisfy the consumption demand of the upper classes (whose numbers are often overestimated in India) for luxury goods of all varieties and take into account the negative impact of FDI on employment in the different segments of the retail trade sector. At a time when organised retail in India is growing at a fast pace anyway and there is no dearth of indigenous capital, the entry of foreign capital which would accelerate the concentration of business in organised retail causing job loss at a massive scale is unwarranted.

Predatory Practices of the Multinational Retail Chains

The case for FDI in retail is often made on the basis of the need to develop modern supply chains in India, in terms of the development of storage and warehousing, transportation and logistic and support services, especially in order to meet the requirements of agriculture and food processing industries. While the infrastructure and technology needs are undeniable, the belief that the entry of the multinational food retailers is the only way to build such infrastructure or upgrade technology is unfounded. That can also be achieved by increasing public investment and government intervention. Moreover, the pitfalls of relying upon an agrarian development strategy driven by food retail chains and giant agribusinesses have already become clear through the experiences of several developing countries like Malaysia, Thailand and Vietnam. Small horticultural farmers find it almost impossible to meet the private quality and safety standards set by the food retailers, which are generally much higher than the national standards. Even the big farmers have to bear high risks while supplying their produce to the food retailers and many get eliminated under the “preferred supplier” system. A FAO paper based on the proceedings of a FAO/AFMA/FAMA workshop states, “Farmers experience many problems in supplying supermarkets in Asia and in some cases this has already been reflected in fairly rapid declines in the numbers involved, as companies tend to delist suppliers who do not come up to expectations in terms of volume, quality and delivery.” (Shepherd, Andrew W., “The implications of supermarket development for horticultural farmers and traditional marketing systems in Asia”, paper presented at FAO/AFMA/FAMA Regional Workshop on The Growth of Supermarkets as Retailers of Fresh Produce, Kuala Lumpur, October 4-7, 2004, available at http://www.fao.org/ag/ags/subjects/en/agmarket/docs/asia_sups.pdf) Moreover, farmers also face problems related to depressed prices due to cut throat competition among the food retailers, delayed payments and lack of credit and insurance. The emergence of such problems in India, especially in the context of the deep crisis that has engulfed the agrarian economy, is totally avoidable.

It is often argued that in case FDI is allowed in retail, the Indian consumers would benefit from the low prices offered by the multinational retailers. It is also argued that if the multinational retailers are allowed to operate in India they would develop an “efficient” supply chain, not only to cater to the Indian consumers but also the international market and therefore our manufacturing and agriculture sector would benefit from their entry. The ability of the multinational retail chains to sell at low prices is often attributed to their “efficiency” in sourcing goods from their lowest cost producers around the world. What underlies this so-called “efficiency” or “cost reduction through better inventory and cost management” is the ability of these retail chains to squeeze producers across the globe using their monopsony power. The sheer size of a giant retail chain like Wal-Mart enables it to exercise buyer power over the producers of all kinds of goods, from agro products to FMCGs, across the globe. If these retailers are to sell goods to Indian consumers at prices, which are cheaper than what prevails today while sourcing their goods from Indian producers, the latter are definitely going to be at the receiving end in terms of declining incomes. In case the multinational retailers import the cheaper goods from abroad, domestic producers would be displaced anyway. It is difficult to understand therefore how the domestic producers would benefit from these multinational retailers.

It can of course be argued that the Indian farmers and manufacturers are going to enjoy access to international markets by supplying commodities to these multinational retailers. However, the experience of the producers, especially those producing primary commodities in the developing world, is not encouraging in this regard. According to a source, while a cocoa farmer from Ghana gets only about 3.9 per cent of the price of a typical milk-chocolate bar, the retail margin would be around 34.1 per cent. (The New Internationalist, http://www.newint.org) The same source suggests that a banana producer gets around 5 per cent of the final price of a banana while over 34 per cent accrues to distribution and retail. Similarly, 54 per cent of the final price of a pair of jeans goes to the retailers while the manufacturing worker gets around 12 per cent. International market access available to the global retail chains do not benefit the producers from the developing countries since they are unable to secure a fair price for their produce in the face of enormous monopsony power wielded by these multinational giants. The growth of global supply chains have only ensured enhanced profit margins for the multinational retailers. The terms of trade for producers in developing countries, especially for the primary products, have been worsening steadily.

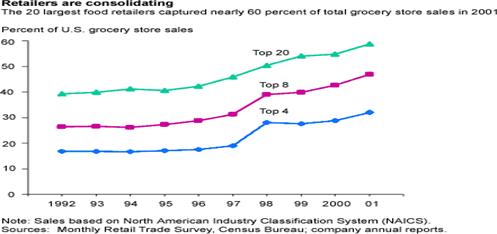

It is true that the entry of multinational retailers can initially make a certain range of luxury goods available at cheaper prices for consumers, especially those belonging to the upper classes of society. Using their deep pockets the multinational retailers can under price domestic retailers thus pushing them out of business. However, once these multinational retailers capture a sizeable market share the consumers are going to be squeezed as well. According to the Economic Research Service, United States Department of Agriculture, the share of the 20 largest retailers in the US had reached 58.7 per cent of total grocery sales in 2001, up from 36.5 per cent in 1987 (see Chart 3). Similarly, the share of the top ten grocers in Europe went up from 27.8 per cent to 36.2 per cent of the European market between 1992 and 1997, according to the retail analysts M+M Eurodata. In the developed countries, a wave of mergers and acquisitions in the backdrop of a stagnant market since the mid-1990s has led to heightened concentration in retailing, particularly in food retail. According to retail analysts PlanetRetail the 10 largest businesses accounted for 40 per cent of modern grocery distribution sales in the US in 2004, 15 per cent of which was for Wal-Mart alone. In 2004, the top five businesses accounted for 29 per cent of total modern grocery distribution sales in the US, 56 per cent in the UK, 67 per cent in Germany and 65 per cent in Canada. (http://www.planetretail.net) The growing domination exerted by a handful of powerful players in the retail sector further enables them to command market power over suppliers and consumers alike and earn super-normal profits as a result. In the context of growing concentration in the retail sector in the developed countries, the promise of cheaper goods being made available to Indian consumers through competition induced by the entry of the multinational retailers may at best be a short-lived one.

Further, the introduction of very large retail chains would push large brands, mostly MNC brands, much deeper into the domestic economy. Since large retail chains find it much easier to negotiate with a few large brands, which are then carried by all its branches, the rich diversity of products and producers that exist in an economy like India would be destroyed. The big branded producers achieve a larger market presence less due to lower costs or better products and more due to their ability to ‘sell’ life styles. Celebrity involvements through powerful media campaigns play a crucial role in ensuring their market dominance. Their surplus is used to power even more advertisement campaigns for the consumers’ eye. It is not an accident that a shoe produced by Nike that costs 5 dollars to produce but sells for 50-100 dollars while Nike pays its entire Indonesian workforce less than what it pays Michael Jordan for endorsing Nike Products. The competition between Coke and Pepsi is not waged through better products or lower prices but through competitive ad-campaigns. The consumer therefore benefits little from this victory of the larger brands while the local domestic producers get progressively eliminated in the process.

Distortion of Urban Development and Culture

The promotion of large retail stores with huge retail space also fosters a different kind of urban development than what we have followed in India till date. Large shopping malls with all known retail chains with their showrooms as a part of urban development is familiar in the US where the consumer lives in suburbs, drives long distances for his/her shopping and lives in a community that hardly knows each other. Instead of this atomised existence and high transport costs, we have chosen a model of mixed land area where every small urban cluster has local markets and local facilities for their needs. It is this model of urban development that is sought to be changed in favour of a mall culture with huge retail chains and branded products. The problem with this model is that it neglects the simple Indian reality where most households do not have cars and need local markets. The malls that have already come up in our metropolitan cities are failing to attract consumers who find local shopping much more attractive. The myth of a huge and fast growing affluent middle class is counter to the reality that this section is still too small to support the remodelling of the urban landscape as is being planned with malls, large retail chains and branded products.

Unfortunately, the failure of the mall-retail chain-brand culture does not only affect the real estate developers and the Wal-Marts. The East Asian crisis was triggered precisely by this kind of distorted urban development, which saw a real estate boom and then a collapse, dragging down developers and the banks that had funded that process. The issue here is not only of FDI in retail alone. This entire model of ‘branded’ products sold through high-powered ads and dominant retail chains coupled with lopsided urban development would promote monopoly in the market, kill diversity and displace small producers on a large scale. This model of development would fail in India, as it has done over much of Asia, but not before it does enormous damage.

Conclusion

It needs to be underscored that FDI in retail is fundamentally different from greenfield foreign investment in manufacturing. While the latter enhances the economy’s productive base, enhances technological capability and generates employment in most cases, entry of multinational retail chains has few positive spin-offs. In fact the negative effects in terms of job loss and the displacement of small retailers and traditional supply chains by the monopoly/monopsony power of the multinational retailers far outweigh the supposed benefits accruing to the organised retail sector in terms of increased “efficiency”. Moreover, India does not have any prior commitments vis-à-vis the WTO to open up the retail sector. Therefore, the case for opening up of the retail sector to FDI does not seem to be justifiable.

Annexure

Chart 1: - Source: Economic Census, 1998, Central Statistical Organization

Chart 2: - Source: Economic Census, 1998, Central Statistical Organization

Table

State-wise Percentage Distribution of non-Agricultural Enterprises by Major Activity Groups |

||||||

|

States/UTs |

Manufacturing |

Wholesale Trade |

Retail Trade |

Restaurant & Hotel |

Transport |

Community, Social & Personal Services |

|

Andhra Pradesh |

23 |

2.2 |

37 |

4.3 |

2.5 |

25.1 |

|

Arunachal Pradesh |

9.8 |

0.4 |

44.8 |

6.6 |

1.8 |

32.6 |

|

Assam |

10 |

3.1 |

46.6 |

5.3 |

3.1 |

28.1 |

|

Bihar |

16.2 |

1.7 |

49.1 |

4 |

1.4 |

24.6 |

|

Goa |

18.7 |

1.3 |

38 |

5.5 |

8.3 |

19.8 |

|

Gujarat |

17.8 |

3.9 |

40.5 |

2.1 |

5 |

25.2 |

|

Haryana |

16.3 |

3.4 |

41 |

3.4 |

3.4 |

27.5 |

|

Himachal Pradesh |

20.9 |

0.6 |

33.1 |

7.8 |

2.3 |

30.8 |

|

Jammu & Kashmir |

20.6 |

2.8 |

45.1 |

3 |

1.3 |

24.2 |

|

Karnataka |

23.5 |

2.3 |

36 |

5.8 |

1.5 |

24.8 |

|

Kerala |

17.8 |

3 |

36.3 |

6.5 |

3.7 |

26.7 |

|

Madhya Pradesh |

22.9 |

1.4 |

36.7 |

3.9 |

1.7 |

28.6 |

|

Maharashtra |

16.3 |

3.2 |

40 |

4.5 |

4.4 |

23.7 |

|

Manipur |

23.8 |

0.8 |

39.8 |

5.2 |

3.9 |

21.3 |

|

Meghalaya |

5.2 |

2.9 |

40 |

10.3 |

1.7 |

32 |

|

Mizoram |

10.4 |

0.3 |

39.4 |

5.7 |

5.4 |

36.9 |

|

Nagaland |

9 |

0.9 |

50.9 |

6.9 |

0.6 |

29.9 |

|

Orissa |

24.2 |

1.6 |

39.4 |

3.6 |

1.6 |

25.9 |

|

Punjab |

16.5 |

3.3 |

39.6 |

3.1 |

1.3 |

30.9 |

|

Rajasthan |

18.5 |

2.8 |

33.7 |

3.7 |

8.8 |

27.6 |

|

Sikkim |

3.7 |

1.1 |

40.6 |

6.8 |

17 |

26.6 |

|

Tamil Nadu |

25.6 |

2.3 |

36.9 |

6.5 |

1.2 |

21.1 |

|

Tripura |

16.2 |

1.5 |

45.1 |

5.6 |

4.6 |

24.5 |

|

Uttar Pradesh |

21 |

1.6 |

45.9 |

3.6 |

2.3 |

22.2 |

|

West Bengal |

24.2 |

4.6 |

41.6 |

4.1 |

5.6 |

16.5 |

|

A & N. Islands |

21.8 |

0.6 |

36.6 |

5.7 |

7 |

23.2 |

|

Chandigarh |

9.5 |

1.6 |

36.5 |

4.1 |

9.2 |

22.2 |

|

D. & N. Haveli |

23.1 |

1.4 |

32.3 |

5.3 |

6.8 |

26.3 |

|

Daman & Diu |

16 |

2.1 |

43.4 |

1.7 |

9.9 |

20.4 |

|

Delhi |

19.1 |

5.4 |

34.1 |

4.5 |

7 |

21.7 |

|

Lakshadweep |

49.7 |

.. |

11.6 |

2.3 |

8.4 |

24.8 |

|

Pondicherry |

10.6 |

1.3 |

40.5 |

6.4 |

3.3 |

28.6 |

Source: Economic Census, 1998, Central Statistical Organisation