People's Democracy

People's Democracy

(Weekly

Organ of the Communist Party of India (Marxist)

No. 21

May 23, 2004

(Weekly

Organ of the Communist Party of India (Marxist)

|

Vol.

XXVIII

No. 21 May 23, 2004 |

C

P Chandrasekhar

Jayati

Ghosh

EVER

since the exit poll results suggested that the NDA government may not come back

to power, the stock markets began to slide.

And

when it became clear that a Congress-led government, backed by the Left, would

actually rule at the Centre, the subsequent market collapse was blamed by the

financial press on fears regarding disinvestment and other possible economic

policies of the new government.

So

much of the presentation of economic news, especially in the financial press, is

oriented around the behaviour of stock markets, that it is not surprising for

people to think that their movements actually reflect real economic performance.

STOCK MARKET AND THE SENSEX

Across

the world, ordinary citizens have been conned by the media into believing that

the relatively small set of players in international stock markets really do

comprehend and correctly assess the patterns of growth in an economy, and that

their interests are broadly in conformity with the economic interests of the

masses of people in those countries.

This

is a deeply undemocratic position. As such, a collapse of the Sensex in itself

should bother very few people.

The

stock market even in the US is neither a significant source of finance for new

investment nor a means of disciplining the managers of firms. It predominantly

is a site for trading risks and is mainly a secondary market for trading

pre-existing stocks or new financial instruments, such as derivatives, that are

based on them.

Therefore,

if anybody loses from short-term swings in the market, it is only those who have

speculatively invested their wealth in trading stocks in the hope of quick

capital gains.

These

features are even truer of the Indian stock market in which few shares are

actively traded, few investors such as the financial institutions, big

corporates and foreign institutional investors dominate, and a small proportion

of the stocks of most companies are available for trading.

What

is more, nobody has inflicted on investors the notional loss that has occurred

in India’s markets prior to and after the elections. Some market participants

have brought it upon themselves and other investors.

It

may be true that dissent over disinvestment was the specific trigger for the

decline on May 14. But if the new government is to respect its mandate there are

a host of policies that it will have to adopt which could result in a similar

collapse of expectations and the Sensex.

FISCAL ADJUSTMENTS

Thus,

the government may have to moderate increases or even reduce the administered

prices of a host of direct and indirect inputs such as power, oil and fertiliser,

in order to alleviate the difficulties being faced by the farming community.

The

implicit subsidy this involves may have to be financed in the first instance by

an increased resort to deficit financing and in the medium term through an

increase in direct taxes on the higher income groups and indirect taxes on

luxuries.

Such

fiscal adjustments may be necessary also to launch large-scale employment

generation programmes to make up for the slow pace of employment expansion and

the consequent persistence of poverty during the 1990s.

Further,

similar

policies may be needed to widen the coverage and increase the availability of

subsidised food through the public distribution system. Increased food

availability at subsidised prices is crucial to reversing the decline in per

capita food consumption and in calorific intake reported by the NSS surveys in a

country where a large proportion of the population is at the margin of

subsistence.

All

of this would be seen as “populist” and “anti-reform”, since NDA-style,

IMF-inspired reform requires a cut in the fiscal deficit, a lowering of direct

taxes, an increase in administered prices and a reduction in subsidies. Attempt

to redress the intensely inegalitarian path of development under the NDA can

therefore be identified as damaging by the “market” and those who advocate

its cause.

In

fact, sections of the media that had celebrated neo-liberal economic reform

under the NDA have already effectively declared that all of the policies noted

above can be a cause for market distress.

The

markets are nervous, they argue, because of uncertainty about the attitude of

the new government regarding the “economic reform” process.

In

fact, the election result that (contrary to all expectations) delivered a

massive defeat to the NDA clearly indicates that certain aspects of the reform

must be reversed.

DEFEAT OF THE BJP AND ITS ALLIES

The

defeat the BJP and its allies suffered in all but three states has been widely

seen as the result of two factors: mass rejection of the communal policies of

the BJP and mass anger with the devastating impact of the neo-liberal economic

policies of the NDA government on rural India and the poor and lower middle

classes in urban India.

Even in Karnataka, the Congress government of that state suffered because of

adherence to similar policies.

Public

anger was all the greater because of the cynical way in which the NDA was

seeking to win another term by misusing manipulated indices of economic

performance and celebrating the gains that a small upper crust had derived from

the liberalisation process.

Given

the nature of this mandate, unless the new government currently being formed

refuses to take account of its full meaning and reneges on its own election

promises when formulating its policies, a substantial dilution and even major

reversal of certain components of the NDA government’s economic reform are

inevitable.

Thus

if few investors who drive the “markets” are nervous about the nature of

economic policy, the error lies in their expectation that economic policies

which benefit them but adversely affect the majority can be sustained in a

democracy where the poor have a voice, even if only at intervals of five years.

Those

expectations were patently wrong and so were the bets based on them. This is not

to say that adopting policies that are less elitist would not guarantee

investors normal profits. They only threaten the abnormal speculative profits

that policies tailored to please finance and big business, such as privatisation,

were expected to ensure.

Seen

in this light, the message that is being delivered by the “markets”, and

sensationalised by the media, should be dismissed as undemocratic and

unacceptable.

It

is also a completely false argument, since it has been abundantly clear for some

time now that stock markets are very poor pointers to real economic performance.

STOCK MARKET INDICES

Stock

market indices are indicators of the expectations of finance capital, and they

can move up and down for a variety of reasons, most of which are not related

even to the current profitability of productive enterprises. They are prone to

irrational bubbles and sudden collapses which reflect all sorts of factors,

ranging from international forces to domestic political changes, and may have

very little relation to economic processes within the economy.

Consider

the latest fall in the Indian stock market. While it is true that some of it is

clearly a reaction to the uncertainty created by the unexpected and remarkable

defeat of the NDA government at the polls, it also should be noted that across

the world, financial markets have been in downswing in recent weeks.

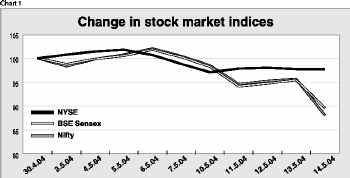

Chart

1

Chart

1 tracks the movement of the New York Stock Exchange composite index, the Bombay

Sensex and the Nifty. The NYSE composite index fell by 4 per cent between May 5

and May 14, and other markets across Europe and Asia have shown similar or even

larger falls.

Much

of this is because of rising oil prices, the failure of the economically and

politically expensive US military occupation in Iraq, and fears of interest rate

hikes in the US.

It

is true that the Sensex index fell by more than 10 per cent and the Nifty index

by 12 per cent over the same period, but this is still part of a more general

worldwide trend of decrease in stock values, and some market analysts have even

described these as necessary “corrections” of the earlier inflated values.

For

the past year, Indian stock prices had been pushed up by large inflows from

foreign portfolio investors, who had recently “discovered” India as an

attractive emerging market that has not yet had a financial crisis.

This

meant that, despite the fact that very little had changed in the so-called

“fundamentals” of the economy, there were substantial inflows from financial

investors that also caused the rupee to appreciate.

Foreign

investors use emerging markets like India to hedge against changes in other

markets; they also like to focus on particular countries in any one period,

where herd behaviour creates a boom and the countries concerned become the

temporary darlings of international capital.

In

India in the recent past, the numerous concessions provided by the NDA

government to such mobile capital also allowed for large super-profits to be

made through such transactions.

Because

the Indian stock market still has relatively thin trading, these foreign

institutional investors made a big difference at the margin, and were

responsible for pushing up stock values well beyond what would be “sensible”

values according to standard international norms of price-equity ratios. This is

typical of the bubbles that have been created by internationally mobile finance

in various developing countries especially since the early 1990s.

It

is inevitable that such bubbles must eventually come to an end, whether through

a sharp burst in the shape of a financial crisis or through a slower and more

managed shrinking of values.

When

this happens, it is true that a lot of players who have put their bets on

continuously rising share values will be affected, but this need not mean that

there has been any other bad news in the economy.

Of

course, it is always difficult to attribute causes to stock market movements,

since financial markets are notoriously prone to “noise” and irrational

behaviour.

However,

more than the actual causes, the implications of such falls are what matter to

most of us, and this is where the mainstream media have been the most

misleading.

STOCK MARKET BEHAVIOUR

It

is usually argued that stock market behaviour is a reflection of “investor

confidence” and this in turn affects important real variables such as

productive investment in the economy, which is critical for growth and

development. This is not really the case, and has become even less true in the

recent period.

Especially

since the early 1990s, the stock market has experienced huge increases and wild

swings, while investment has not shown any such volatility and indeed has barely

increased in real terms.

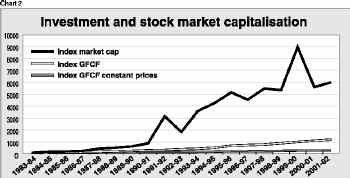

Chart

2

This

is evident from Chart 2, which shows the index of stock market capitalisation in

India since the early 1980s. Stock market capitalisation increased by around

four times in the decade 1991-92 to 2001-02, with very large fluctuations in

between.

Chart

3

By

contrast, total gross fixed capital formation in the economy increased much less

even in current prices, and in constant prices it barely doubled. More to the

point, Chart 3 show that the large swings in market capitalisation were not

associated with any commensurate changes in investment, suggesting that the

financial markets dance to a bizarre tune that is all their own, and do not have

much impact on real investment in the economy. This is very important to

underline, because the reason that we are all supposed to be concerned about

stock market behaviour is because of its supposed effect on investment. In fact,

it is really only those agents who are dependent upon the return from finance

capital who are affected, while real investment depends upon many other factors.

The

other impact that movements in the stock market have nowadays is on the exchange

rate, especially since so much of the change is caused by the behaviour of

foreign institutional investors.

Their

movements over the past year have helped to build up the RBI’s foreign

exchange reserves to an almost embarrassing amount, partly because their inflows

are not being used to increase productive investment, and partly because the RBI

kept buying dollars in an effort to keep the rupee from appreciating even

further.

FOREX RESERVES

While

the large forex reserves may have provided a macho feeling of false confidence

to some, in reality they were a reflection of huge macroeconomic waste, since

they implied that the capital inflows were not being productively used.

They

were also expensive for the economy to hold, since the interest received on such

reserves by the RBI is typically very low, whereas the external commercial

borrowing by Indian firms in the current liberalised environment was at

significantly higher interest rates.

In

this background, some dilution of the forex reserves may even be welcome. Of

course, if the current outflow turns into a capital flight, which is also joined

by Indian residents, then clearly the situation can become more serious. Such a

possibility is now more open because of all the recent measures liberalising

capital outflow that the NDA government brought in the closing months of its

rule.

The

new government may have to address some of these measures quite quickly, to

prevent excessive capital outflows, which can then become another means of

pressurising the government on its economic policies.

But

in all other respects, there is not reason for the new government to concern

itself with keeping the financial markets happy or letting its behaviour

influence economic policy.

The

people’s mandate is for a redirection towards more progressive policies, which

will also deliver more sustainable growth. Financial markets, if they are at all

sensible, will not only have to respect that mandate but also realise that that

is also the only route to political and economic stability.